We have all heard from our parents or grandparents how great the Muslin used to be. Like how you can fit an 18-foot saree in a small matchbox or how a chunk of Muslin can fit through a small ring.

But how did something so delicate come to be made? Was it as great as the people claim? How did it perish? Are the Muslin people buying now the same as before? There are a lot of questions, and we decided to dig out the history of Bengal Muslin to find out.

The History of Bengal Muslin: Why Was Muslin So Special?

The origin of Muslin dates back about 400 years ago. Although most people will tell you that “Muslin” was named after the town of “Mosul” in Iraq, that’s because they think the fabric originated there. But we believe it was named after a small port town in India, “Machilipatnam.” Back in the day, that town was more commonly known as “Maisolos.”

Woven from cotton that only grew on the banks of the Meghna River, the first Muslins were made in ancient Dhaka. Muslins were sold throughout the regions in the market named “Aarong,” and the most famous Aarong was in Panam Nagar, Sonargaon.

Although Muslins were also produced in parts of India, the Muslin made in Dhaka was the finest. “Phuti Karpas,” the cotton tree unique only to the Dhaka region, was the secret behind it. Lines of Phuti Karpas trees grew on the bank of the Meghna River. The British tried to grow them elsewhere, but they failed.

Everything about the Dhaka Muslin was special. By everything, we do mean everything.

Only the best of the Phuti Karpas seeds were planted with ghee. Then, it was hung in the kitchen to be heated. Every tree was properly loved and nourished. When it’s time for the harvest, the weavers use the jaw of a catfish to comb the raw cotton.

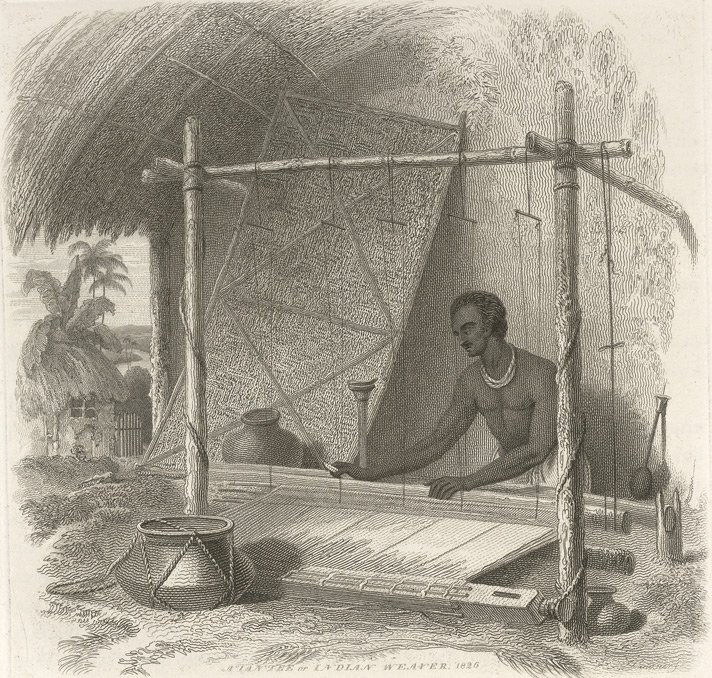

The threads had to be spun in humid weather with delicate touches. That’s why only the young women were allowed to do the job with bowls of water beside them to moisten the air. Or often in the middle of the river, on boats. The job was done only at dawn or dusk because the result wouldn’t be the same in the presence of bright sunlight.

The weavers used the “Dhunkar” to separate the lightest cotton fibers from the heavy ones, which would be spun into Muslin thread later. This process eliminated most of the harvested cotton, and the lightest fibers were selected. Only eight grams from a kilogram of cotton were used.

This is how, with all that extra care and special attention, it was possible to create something extraordinary. Muslins were so light and delicate, it was also called “Baft Hawa,” which means woven out of thin air.

Was Muslin Famous Throughout The World?

Muslins were the most expensive and desired fabric all over the world. They were exported in bulk to every corner of the world. The Babylonians, Egyptians, Arabs, Europeans, and Chinese were all in love with it.

But the Europeans were the ones who fell for Muslin the hardest. In Great Britain, the Muslin completely changed the taste in fashion of the aristocrats. Naturally, Muslins were something that only the rich could afford, and within no time, they became a symbol of status. One yard of Muslin was priced at 50-400 pounds, which is equivalent to 7000-50,000 pounds now. No wonder the Greeks considered Muslins the clothing for the Gods, as they clothed the statues of their Gods with it.

Muslins were used as gifts from Indian emperors to other rulers to persuade them. They were also traded for exotic items like ivory, rhinoceros horns, etc. Travelers who visited Bengal in that era were highly impressed with the techniques of the local weavers.

But there’s also a flip side to the coin. Muslins were thin and transparent, well, maybe a bit too much. To some people, wearing Muslins was equivalent to wearing nothing at all. The men and women who wore them were reprimanded for showing too much skin.

We found one particular story that we’d love to share about this: Zeb-un-nesa, the daughter of Aurangazeb, once wore seven layers of Muslin to attend her father’s court. But still, she was scolded by her father for appearing virtually naked.

Even after all the controversy, the Muslins were loved and made with love. They were truly a fabric that was created out of thin air.

How Did Dhaka Muslin Disappear?

By the time the British were obsessed with the Muslin, the Mughals’ reign finally ended. Now, it was the British who were to rule Bengal.

The East India Company had its eyes on the Muslin and many other things. Since Muslins were “the thing” in Europe, they tried to maximize their profit. How did they do it? By forcefully producing the Muslin in bulk. While they were at it, they also underpaid the artists.

But the Muslins were something that you did not trifle with; the creation needed appropriate time, skills, and hard work. To meet the demands of the British, the weavers were overworked and underpaid, leaving most of them in debt. Also, the weavers were forbidden to sell the Muslins to others apart from the British.

To top it off, the British paid them in advance for the fabric, but if it wasn’t to their liking, the weavers had to pay them back. Slowly, the weavers could no longer keep up to pay off their debts and eventually lost everything.

But what killed the art completely was the cheaper, lowly versions that were created by the British textile barons. They wanted to make the Muslin themselves, so they learned the process and used their cheap cotton to replicate the Bengal Muslin.

It did not even come close to the originals; however, it spread across the British market, and the demand for the original Dhaka Muslin slowly died.

To survive, the weavers who used to make Muslin changed their occupations. At some point, no one knew how to create Muslin anymore.

And that’s how one of the most exquisite creations of Mankind got lost in time.

Bengal Muslin: The Second Coming

The Phuti Karpas went extinct, the weavers switched jobs, and the Muslins were lost.

Still, there were Muslins made in Great Britain and India, but they were just different.

But the Dhaka Muslin was not forgotten.

The Jamdani, cherished by the women of Bangladesh, is considered a descendant of the Muslin. But where Muslins had a thread count higher than a thousand, Jamdanis barely reached a thread count of 100.

In 2015, the Bangladesh government started a project to revive the Muslin to its past glory. The project successfully managed to regrow the Phuti Karpas tree after extensive research. But the higher thread count, which made the Muslin unique, seems impossible to reach even with the latest technology.

However, the dream of reviving the original Muslin is not dead but rather materializes strongly with time.

Final Thoughts

The history of Bengal Muslin is undoubtedly a tale of both glory and tragedy. It serves as a powerful reminder of the fragility of heritage. The impact of the Bengal Muslin would surely change the dynamic of the textile industry if it existed to this day.

The good news is that the spirit of Bengal Muslin still lives. Someday, the effort to revive the Muslin will complete its mission, and we will experience a forgotten culture. Until that day, we can only hope.

“Hope is a good thing, maybe the best of things, and no good thing ever dies.”